Third chapter

Wherein the writer begins the wondrous story of his purchase, from the possession of a foreign Prince, of a young mestizo, who has to serve Jackal as a slave; wherein he furthermore makes mention of his camping experiences.

It did not take long before Jackal and I, both completely undressed, laid in each other’s arms in a breathless embrace. We had laid down on the beautifully arched cedar resting bed, decorated with Persian gold, bought in Pompeii on one of my foolhardy journeys, piteously broken in the middle but carefully repaired, and which, with a probability bordering on certainty, had belonged to the young love companion of the Roman emperor Titus.

We resided in my Chateau La G., in the R. valley, a pleasant place to stay in autumn, in the tower chamber, which was easy to heat, and offered a view over almost the entire little town nearby.

At first I could not speak from emotion, as I felt Jackal’s cool, supple boy skin that smelled of fresh hay and Russian leather against my paltry limbs that shivered from the fever of love. It was a happiness that frightened me: how could this Mercy have been granted to me, one who was untimely born, who, with all my attempts at penitence, my devotion and my pilgrimages, had always led such a reprehensible, sinful, yes, from a moral point of view, repulsive life? I had committed many of my sinful, deviant excesses on my journeys, and my thoughts now went back to them, with deep remorse and regret. How much I had desecrated my own body and, in so doing, that of the Creator! If I deserved anything at all, it had to be the eternal, hellish torture of irrevocable Judgment, and in no way the delight of this bed of love. I yearned to be judged and chastised for my words and deeds at this very instant. If the Most High imposed such a punishment already in this life, could He charge Jackal with the execution of it?

‘When will you finally really hit me, Jackal?’ I whispered. ‘You are a man, aren’t you, and not some kind of queer? When will you give me a sound beating again, like there is no tomorrow?’

Jackal smiled. ‘Do you remember, Jackal, how you handled that unfaithful Mestizo back then, whom I had bought for you in a foreign country? If you hit me like that, I mean the way you chastised that adulterous creature of love… Oh, Jackal, how madly did I love you then. That was when my love had only really begun. Do you remember?’

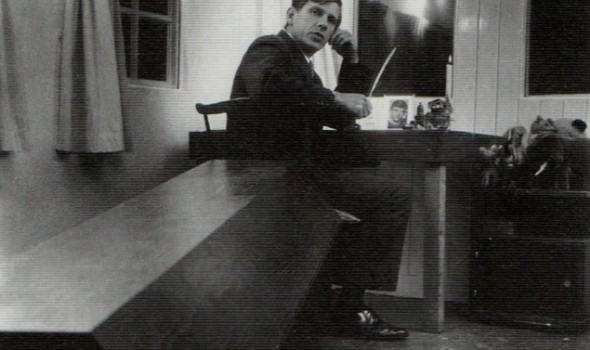

‘Not exactly,’ Jackal said softly. He now relaxed his entire, mighty, lazy body, and he laid back, placing his hands behind his neck, the way Boys always laid back at summer camp after chopping wood or days of pointless path-finding, or after having conducted some useless research about indistinct animals living in the wild that were no longer there: near his tent, such a boy then laid back on the short, uncut grass, which had already turned to hay because of the drought, whilst his largely innocent Boyness was clearly outlined in his thin cotton pants, smeared with lichen stains. A cursed, but indelible memory stopped by and came over me: of a boy who once, in my youth at a summer camp, had laid like that, backward on the ground, in all his ignorant shamelessness, half hidden behind a tent… where I had spied on him, each time he was lying there, from under the curtain of another tent… when I had been maybe ten or eleven years old; the boy possibly of the same age, with the odd name Wijnand. With all my desperate, dark, cruel longing for his body and his voice, I had, for days and days of emptiness and loneliness, waited for an incident, anything, that could lead to his humiliation and punishment and his subjection to severe pain. And that longing had been fulfilled – truly the only time in my life that any of my sinful desires had ever been directly realised. I would have liked to tell Jackal about it immediately, so that the cruel incident of so long ago, which I had not shared with anybody until now, would give him the same, dark ecstasy as I had felt back then, on that particular afternoon, years and years ago, which had overwhelmed me for the rest of my life.

‘What is a Mestizo, actually?’ Jackal wanted to know.

‘They are often exceptionally beautiful boys,’ I started. ‘A Mestizo is born of an Indian mother, but conceived by a white man. They can’t count, but they are said to be very diligent. That’s why I bought him for you, when I was most deeply moved by his naked beauty, although his master did not want to give him away, not even for the highest bid. I had a book with me… But let me start from the beginning…’

‘He was unfaithful, you said?’ Jackal asked. ‘To whom?’

‘He would one day be unfaithful to you, in his randy, adulterous audacity, Jackal, with that sluttish, young blond bear of a mailman in V., but nobody could know that at that time. He was not even in the country yet! He was still in a foreign, faraway country. He still belonged to an entirely different person. He didn’t belong to you and you hadn’t even laid eyes on him! But I saw him, in the court of the young Prince, whose guest I was, and who overwhelmed me with generosity. There were also boys, dressed as girls, dancing with shiny jewellery and rings in their cute ears.’ I laid my hand on Jackal’s dark Member, and cupped it loosely and tenderly. While speaking the last sentence, Jackal’s breathing had quickened a little, and his Member, although not yet in a state of alarm, let alone ready to fire, had nevertheless become distinctly more robust.

I thought it miraculous and, at the same time, heavenly that I was allowed to tell him what we had been through together, accurately and faithfully, whilst he nevertheless already knew everything I was about to recount.

‘One day, Jackal, I will write everything down. It will become a book which contains everything, everything regarding our Love: I will write it down so beautifully that the rich, in their lascivious houses in the hills, will have it read to them by their slaves, whilst they are seated in front of an early fire, with a strum of music and strings played, not as a melody but as a backdrop: a dark lute, or a deep, sweetly moaning flute made of soft fig wood. The night falls, but the rich man, in his hedonism never satisfied, and the slave, having become tired and hoarse from reading, is generously plied with enticing beverages, such that he may continue to read without his voice failing him.’

Jackal smiled again, and nodded. In silent, grateful ecstasy, I started, at first hesitating, but gradually with a bolder, moving voice, to evoke the beloved story for Jackal, which would once again have to make him yearn, and make him gluttonous for love and through cruelty intemperately randy.

‘Listen, Jackal. I traveled far away, alone, and I arrived in a remote, strange country, where I enjoyed the hospitality of an opulent Prince, who possessed nearly everything and ruled all the land. They were a completely foreign people. At night, seated in front of the fire, the Prince asked me everything about my country, and how people loved one another there, and we talked until the deep of night. The Prince was still young, and beautiful, and powerful, and rich, but he was also very Lonely. He, however, never mentioned that.

I was given a chamber for the night in the guest pavilion of the princely palace, and lay awake for a while, listening to the wonderful, far-away music and the dancers’ voices, and I was still full of thoughts about the wondrous things the Prince had told me about his faith and his love.

I slept deeply, for a long time, and the sun was already high in the sky when I awoke and heard feeble noises outside which I could not identify. I stood up from the lush, golden, lily-shaped bed that the Prince had ordered to be swiftly carried into my room on the previous evening after my arrival, and stood at the opened window. My breath was taken away by what I saw, Jackal. A small, round pond was situated in front of the pavilion, where a fountain poured out its crystal clear water, softly splashing. Sitting crouched at the well was a boy, drawing water into two beautiful copper buckets that seemed to be made of gold, so shiny were they. He was almost naked, that boy, Jackal. He wore only sandals on his naked feet and, held tight over his groin by thin cords, a very small triangular cloth of supple, almost transparent leather. I looked at him half from behind, half from the side, but his face was turned somewhat in my direction, such that I could, to a great extent, discern his countenance. I knew two things, Jackal. I knew that I would do everything within my power and give everything to be able to bring him back for you. But I also knew that I had seen the same boy face before, once, long, long ago. It could not have been the same boy, because the memory was from too long ago, Jackal. But it was the same face as that of the boy that I… I once had a boy… had him… It was in a… Are you asleep?’

‘No.’

‘So I took with me that young, almost naked Mestizo at the well, for you, Jackal. But he looked like a different boy, a boy from long ago. Do you know what I did to that boy, cruel, sweet beast of mine? Shall I tell that one first…?’

The sound of Jackal’s moan set off a jubilant resonance in me, because I knew that he was longing and eager to hear the story that I had never told to anyone, that I had carried with me in the deepest secrecy for years, but that I would now reveal to Jackal, and only to him.

‘What I did then, I would do again now, Jackal, countless times, for you, always, again and again…’ I panted lightly. I looked at Jackal, who was smiling again, and now I caressed his huge club of love, which rose with a slight shock with each caress, only to descend slowly again. Jackal felt no shame, and he smiled at me, and my own shame, which had, for such a long time, covered my secret with silence, parted from me, and I could tell him about the incident that I had kept a secret for so many years.

How long ago did it happen? I think I was ten or eleven years old, attending some kind of summer camp. I do not remember if it was a camp organised by my school, or by a club that wanted to bring young people into closer contact with nature. I actually believe that I, like always, did not belong there – I mean that my stay and participation were not in accordance with the regulations: I did not attend the school where all the other boys of the camp went, and by no means was I a member of the youth club that would have organised this and that. I think that a good acquaintance of a friend of a neighbour had managed to place me in that summer camp for boys, probably in the nick of time, a few days before the start of the summer holiday. The camp lasted three weeks, but I stayed only nine or ten days: the period during which, for some reason, the place of an absent or sick boy was vacant.

(Tented camps in a valley, and then a hurricane, or a river dam that breaks, and immerses the families of eighty-one boys and eleven youth leaders in grief – I don’t know why, but I always remain unmoved whilst reading such reports, breathing a little faster at the most; when a rat or a dog or a cat is run over, it moves me a thousand times more.)

People also sang at the camp. None of the youth leaders were pretty: they had small mouths, and some of them drooled.

One often went hiking, in large groups, where one had to walk two by two, and the leaders tried to turn hiking into a kind of march, setting the example by making their arms swing out emphatically, in time with their steps.

During the evenings we were read to from a book, in which it was explained how stupid the people from long ago really were, because they believed in all kinds of little gods and even in God, until they had gradually come to their senses and started to measure the temperature of gases.

The camp did not only consist of tents: there were also at least two wooden barracks, where one was not always allowed inside and which remained reserved, mostly for use in inclement weather.

One afternoon, I was alone in one of these barracks that had high, dusty windows, through which one could not look outside. The weather was only moderately good: it was windless and overcast, with brief spells of extremely light, barely noticeable drizzle. Almost everyone at the camp had gone, participating in one of the countless, inevitable hikes. I do not remember how many people the camp counted. In one’s memory, one always imagines huge numbers, but the total number of persons, including the staff, probably did not exceed three dozen.

Neither of the barracks had been meant as living quarters. Rather, they were large sheds that had had something to do with poultry farming, as the entire encampment stood on the site of a former chicken farm. One barrack was completely barren and empty, but the other, where I was that afternoon, had, on one side, been very minimally equipped as a day room, possibly for gatherings of the local boy scouts: a wooden barrel and an empty wooden spool, put down like a mushroom that had once been wound with underground electrical wires, served as tables, and all kinds of crates and boxes served as chairs, and there was even a sort of a counter or bar, constructed from orange crates and overlaid with plywood. A few worn smoker’s ashtrays made of enamel or porcelain with tobacco advertisements on them were placed on that counter and also elsewhere on the other very basic furnishings. Empty bottles and jam jars without labels, which apparently could no longer be returned for deposit money, were placed on the ground. Some kind of statuette that was made of stone or porcelain, about a quarter of a metre in height, or possibly even significantly smaller, stood on the bar, close to the wall.

I was alone in the barrack, and in my hand I kept a thin, flexible willow branch, that I had cut off somewhere and that I uselessly let swish about, and that I used now and then to deal out welts on the wooden walls and random objects that I took for targets.

I can now surmise with certainty that, apart from me, no one else was present at the entire camp that afternoon other than a boy and a leader. Of all the boys that comprised the camp, not one of them had handsome looks or anything cute about them, except for one boy, and exactly this boy had not left with the others but had stayed behind in the camp, just as one of the leaders had. This boy, who carried the remarkable name ‘Wijnand’, did not usually participate in strenuous games or long hikes, because he was said to have an ailment, asthma, or diabetes or weak lungs or a whistling heart valve – I do not remember what it was: maybe he has already died long ago, but I still suspect, I do not know why, that, in reality, there was nothing wrong with him.

He was exceptionally beautiful, this Wijnand, in any case according to the standards of worship that I upheld at my tenth or eleventh year of age and, therefore, I had never dared to approach him. In a crucial way he was different from the other boys, and like me, did not belong to the group, although in a completely different way than me: I believe that he was from a somewhat well-off family, at least compared to the paupers from which everyone else descended, including me, and it could possibly be that his parents had a say in the camp, which they might have supported financially, as the boy enjoyed a certain cautious protection and was spared in all kinds of ways.

His appearance, which I can still summon with photographic clarity after so many years, attracted me in an imperative and inescapable manner, which confused me profoundly. Despite his somewhat fragile, vulnerable physique and his clearly shy expression, I attributed the brute, unpredictable power of an animal to him, and secretly gave him the name Brother Fox, whispering it in the darkness of my tent in my camping bed, while I touched myself thinking of him. In my opinion he looked like a mighty fox, and I revered him. His face was narrow, with deep-seated, grey eyes, and his dark, lank hair, here and there slightly discoloured by the sun, was cut short on the back and on the crown, but kept fairly long on the front, where it often fell very elegantly over his forehead. He had a big, sharp nose and a distinctly chiselled mouth, which was sturdy in comparison to the rest of his slender face, and readily showed his somewhat irregularly implanted, razor-sharp fangs. I believed he was older and stronger than I, but now suspect with assurance that he could not have been older, and that my imagination that had made him physically stronger than myself, was completely influenced by my desperate reverence for him. (Only many, many years later have I understood that he, this Wijnand, sought me out and must have been attracted to me, but I could not conceive it, and was avoiding and fleeing him in all my desperate longing.)

He wore somewhat better clothes than we did, mostly finely striped shirts, which were still quite expensive when they were in fashion, and short, black cotton trousers, carefully chosen or even tailor-made, and his shoes as well, were made from expensive, supple, unpainted leather a model of mountaineering boots which city dwellers took for luxurious footwear. I worshipped his expensive, moss-green stockings, which boys in those days wore just up to the knee, and which may or may not have been decorated with wool tassels, one of which he sometimes lowered with a casualness that completely overwhelmed me.

That afternoon he had, as mentioned, stayed at the camp, but I did not know where he was. At least one of the leaders must have stayed as well, but where he was – in the barrack, in one of the tents – I also did not know. I had stayed behind on account of some pretext: that my foot hurt, supposedly injured after a jump, something of the sort.

In the barrack, where I was alone, an almost perfect silence reigned: the drizzle made hardly any sound on the corrugated iron roof. I walked around the well-trodden, dry clay floor, and hit a willow tree branch with force against the wooden walls, such that the green skin on the tip of the branch was stripped. I stopped in front of the wooden crate counter and struck forcefully the plywood countertop that was painted in a dull black, ink-like watercolour as I approached the side of the barrack that had been set up to be a day room. Fine dust whirled up after my blow, and the ashtrays and the statuette danced and wiggled. The ashtrays remained more or less in their places, but the statuette moved in my direction towards the edge of the counter. Again, I struck my branch on the poor, thin plywood surface; and the statuette, hopping up a few millimetres and turning slightly on its axis, shifted again towards the edge, while the ashtrays stayed more or less where they were. I struck the withered, loudly resonating wood a third and fourth time. With the fourth blow the statuette reached the edge, and a small part of its stand went over, but after a few wobbles, it remained standing. I hit the top for a fifth time, now harder than any of the previous times. The statuette jittered, shifted along the edge, toppled, and fell. Most of the barrack floor consisted of tamped, smoothed out clay, but all around the counter they had made primitive flooring that consisted of evenly placed bricks, apparently originating from a demolition. The statuette fell backwards onto this brick surface, and broke into three big pieces, which I gathered and fitted together. I managed to put together the pieces in a precarious and unstable configuration, and to put down the statuette in its entirety in such a way that it remained standing, such that, upon superficial inspection, the damage was not even visible. At that moment the barrack door opened, squeaking loudly. I stood motionless and had to hold my breath for a moment: Wijnand stood in the doorway, curiously looking about whilst his eyes adapted to the faint light. He must have walked outside for some time, in the drizzle, because part of his hair was soaking wet, part of it was half-drenched, and covered with fine drops of water. He entered, closed the door, and slowly walked towards me. I stood frozen, expressionless, but I also knew, in immense depth of a suddenly all-encompassing knowledge, that something decisive would unfold in my life, which I would be unable to change, because it had already been inescapably predestined before all time.

‘What are you doing?’ Wijnand asked, still standing at a short distance from me. It was as if at first I only saw the movements of his mouth, and only much later heard the sound of his voice and understood his words.

‘I am looking at all kinds of things,’ I answered hoarsely. ‘Don’t you think that’s a funny statuette?’ Wijnand walked towards the counter and stretched his hand towards the statuette. At that moment, I heard someone outside, at the barrack door. Once again I knew that everything that would follow was now immovably definite and already dictated before the dawn of time.

The door opened. Only the youth leader that had stayed behind at the camp was standing in the doorway. He was ugly, and I remember considering him to be old, the way young people think everyone is old who his ten years their senior. It is possible that he was not much beyond his late twenties, but there was already something bony and worn out about him, in his somewhat saggy clothes, and the black beret that he wore tightly over his head completed his nameless insignificance.

‘So? What are we doing here?’ he asked in turn. Little saliva bubbles were visible at the corners of his mouth. He stood very close to us. At that very moment the broken, put-together pieces of the statuette crumbled in Wijnand’s hands and clattered down onto the counter and floor.

‘He is smashing beautiful statuettes, that sort of thing’, I said. ‘Probably because he’s bored.’

It was as if the walls echoed my words, and gave them an even more imperative clarity. Wijnand turned around and stood before us, his hands displayed helplessly. His bestial, big boy mouth trembled: he apparently wanted to say something, but he had to swallow first. With a few quick movements, which I did not have to think out because they had been ordered already before the creation of all things, I grabbed him, pulled him towards me face down, forced him to bend down, locked his neck between my legs, and with a swift gesture handed the youth leader the willow branch that I had clenched between my teeth during the short struggle. I knew that nothing I did was ambiguous or required an explanation, but that the youth leader had wanted and desired the same unavoidable thing as I from the very first moment. Without hesitating for even one second, he accepted the branch from me. The door of the barrack, which had remained open, now started to close, as I had always known it would because of the draught, slowly at first and then faster, and finally flew shut with a firm slam.

‘Why did you do that?’ the youth leader asked, but it was not at all a question that required any answer. Wijnand’s voice, which reverberated up to my groin through the skull of his bones, started to stammer something, but the youth leader was already making the willow branch whistle through the air and, with brute force, intending to inflict as much pain as possible, let it land on the tight seat of Brother Fox’s black pants. A cry rose from his throat, part scream and partly turning into a fierce sob, but the next welt already came down. I now smelled the dazzling fragrance of Wijnand’s boy sweat, and on the inside of my thighs became aware of the warmth of his tender yet muscular boy body. I pulled up his waistband with both my hands to make the thin cotton of his short pants tighten to the utmost over his small, hard and high buttocks.

The youth leader struck another blow, with almost athletic force, and Wijnand’s crying passed into a hoarse roar that reverberated through my upper legs into my whole lower body. He seemed to have regained breath only then to try to wrest himself free. I kept him locked down with all the force I could muster, but I also knew that it was impossible for me to ever let him go before I…

The youth leader now hit a little lower, just above the edge of the legs of Wijnand’s short trousers, which I still held tight as a drum skin. The boy’s electric cries became fiercer and higher in tone. Jerking his neck and shoulders, he did everything he could to pull out of my grip, while he tried to protect his bottom with his hands.

‘He really should get it on his bare buttocks,’ I spoke slowly and loudly without looking at the youth leader. He now let the next blow strike across Wijnand’s naked upper thighs, with the stripped extremity of the branch, then again a little lower, with truly unmatched calculation and cruelty. I felt his entire body rise in a wave of pain, whilst his cries became shriller, so hoarse they almost whistled. His head was banging about between my knees, in a frenzy, and his wet, warm hair sprinkled my bare legs. ‘I loved him, Jackal. I loved him… finally, finally I understood… and I kept thinking the same thing, the same words over and over again: Fox song, fox song… that is what I kept thinking, Jackal… Fox song… and then… My groin flooded with my own love-juice, Jackal, you know that?’ Do you like what I am telling you?’

‘Yes…’ I now manipulated Jackal’s member with all the ingenuity that love availeth.

‘Jackal, listen… That boy, back then… I had him whipped, but for whom…? In whose name could I have him whipped? Back then I had… nobody… I was alone in this world… I did not know you yet, Jackal. But now… I know boys like Wijnand, now… I know where they live, and what they’re up to together, Jackal… I know where they go to school, those little whores from technical school, with their whorish arses… We take them home, one at a time, or in pairs, two friends, of which one has to watch while we chastise the other, the pretty one. His velvet trousers go down, Jackal… We tie his hands behind his back… And I whip him for you, for you, Jackal… You are dressed from head to toe in tight, dark leather; you are also wearing leather gloves… You pull his buttocks apart, for me, for my whip… a thin riding whip… and I whip him, I hit him… in between, in between… that little whore… right there… in his crack, on his small notch and on his blond boy purse underneath, his whorish purse… with the thin whip… that he… ’

Jackal’s lower torso jolted, and from his silent barrel he now fired: two, three, four times; the first shot went over our heads and landed somewhere behind us, in the bookcase. His mighty body vibrated some more, and then lay silent. He had closed his eyes, his head tilted a bit, with his face turned halfway towards me. It seemed as if he were already sleeping . I touched the threads of the wondrous web of love that he had just spun with his white blood, which formed a net around his blond groin, in which I hoped and prayed and longed to be held forever as a prisoner of Love.

At first I did nothing but look at Jackal’s face. I could now ask him to touch me, and tell me the things that could for some moments cure my deadly wound, but I decided not to interrupt his holy slumber. I touched myself, cautiously speaking my words of worship, very quietly, almost inaudibly, while repeatedly halting, to listen to his slow, deep, satisfied breathing. Outside, the evening turned to dusk. My gaze rested on his mouth in the twilight. I could not find peace in the thought that he would have to die one day.

—

Many thanks to co-translators Jaason von Banniseht en Mireille Mazard