Second chapter

Wherein the writer exchanges thoughts with his friend Jackal about the fate of mankind and modern means of communication; wherein he makes oral profession of his ecstatic, sensual love for Jackal.

When Jackal’s parents got their first television, the device was not purchased from an ordinary television merchant, but delivered by a film projectionist from a cinema. The purchase was combined with that of a large sideboard, though this piece of furniture and the television were not attached. The sideboard had such a strange shape and appearance that a furniture maker had to be called to adjust the other pieces of furniture to the sideboard by gluing imitation wood carvings to the legs and the backs of the chairs.

The television had a clear image for about five weeks, until the end of autumn, when it started to display a lot of falling snow, only to become permanently silent more than a month later, blind and dumb. The film projectionist had meanwhile moved to a completely different city. The television and the sideboard, though acquired as a single lot, did not belong together, but furthermore the television set itself turned out not to be a single unit: it consisted, rather, of two halves, each from a different brand, such that any warranty or claim would be in vain.

Jackal’s father, who was very experienced in these kinds of transactions, also never missed an opportunity to buy old radio devices at the market for a few guilders, which he dismantled and stripped of the big, old-fashioned tubes that were often coated with golden or silver metal, and which, in the early days of telegraphy, were called lamps, and, indeed, bore a certain resemblance to electric light bulbs. He looked at and inspected each of the lamps most carefully, especially the ones that had somewhat distinctive shapes and sizes, and ones that carried a second, smaller lamp on top. These compound lamps, in particular, drew his undivided attention: he gazed through cracks in the metal coating and held them to his ear, shook them with the most cautious, careful movements, and listened near the blinded heads of the lamps to the faint murmur of the wires, as if he could still hear the far-away transmitters of strange countries and peoples from long ago. All the lamps were finally placed upright in feeble cardboard boxes, and stowed away in the attic. If one lifted these boxes without exercising extraordinary caution, the bottoms would fall out and the lamps would rain down upon the bare attic floor, at risk of shattering.

‘Those devices never worked’, Jackal said bitterly. ‘None of those devices ever worked.’ He shook his head.

‘Big devices, I suppose?’ I asked.

‘Huge, colossal devices. Gigantic encasements.’

‘Yes. But you have to take into account that a device that does work would probably soon cost, say two hundred fifty guilders,’ I argued. ‘And that would not even be a big device, but one might just as well say a small device, actually. Such a very large device that doesn’t work, for, let’s say, two guilders and fifty cents, that’s not expensive at all, really. Did he also make his own wool carpets on a 429.50 guilders costing do-it-yourself knitting device or six terms of 99 guilders 75 cents within six weeks Your own 85 x 11 centimetre hearth rug bigger sizes on demand?’

‘No, not that,’ Jackal mumbled dully.

‘What a childhood,’ I stated. ‘I bet it rained all the time?’

‘On Sunday afternoons, I don’t know if I ever told you this,’ began Jackal, ‘my father and mother went upstairs to the bedroom. The door was locked. For half an hour, an hour, something like that, I don’t remember exactly. I don’t know what took place there, but afterwards, when they came down, a mood hung, a doom, something so disastrous in the house, impossible to describe. I forgot when it was, but I believe there was almost an entire year in which I cried for days on end.’

‘He was not ever allowed anything,’ I established, very pleased with my own cleverness.

‘You suppose so?’ Jackal sneered. ‘Yes, I still remember hearing my mother say one day, I don’t remember where or to whom: “And then he wants it again in the morning.” ’

‘When you’re with me you can always have your way, Jackal. I want to be a mother to you, who always will allow, you. I mean, always, whenever you want. I’m your bride, your slave, you may look at pictures in a book when you possess me and ride me, just as you please. We can build a small pub table that fits exactly over my neck and shoulders, so that you won’t have to suffer hunger and thirst during your wonderful ride through the land of love. Jackal, I don’t know how I should tell you this, but I am absolutely crazy about you. I’m a man, am I not, but if you stand in front of me, I don’t know why it happens, I want to give myself to you like a woman, with body and soul, honestly.’

Jackal was quiet. I was really completely at a loss for words, but with a fatal urge, I babbled on. ‘Surely, many of your toys were broken in your childhood, Jackal.’

‘Huh? I once got an electric railway train,’ began Jackal. ‘Did I never tell you this? My parents had apparently chanced upon a second-hand one.’

‘From people whose child had recently died,’ I said. Jackal did not react to my words, and, for a brief moment, it seemed as if, what fortune, he had never heard me utter the sentence at all.

‘But it didn’t come with a transformer,’ he continued.

‘Right,’ I said. ‘And that’s how it got connected to the electricity in the wrong way, and for a short while it worked, and then the engine burnt out.’

‘How do you know that?’ Jackal snapped. ‘Have I told you this before?’

‘No. Ah, Jackal. I love you so much. You shouldn’t tell me these stories. I can’t bear it. It drives me crazy. When was that? How old were you? Seven, eight years old?’

‘Eight, I think’, said Jackal. ‘It occurred around the time of the Pinocchio book, and the dollhouse that my sister got from my father.’

‘Didn’t you get a dollhouse yourself?’ I asked. At the very moment I said it, I really did not want to live anymore, but I was also mad with a fear of dying. What reason or excuse could God invent to have Mercy on my poor soul? ‘Yes, sure, Thou rejectest me’, I spoke inaudibly, ‘but hast Thou not created me as I am? Canst Thou reject me while I am precisely the way Thou hast made me and declared me to be?’ I had the imperative feeling that there were only two possibilities: either Jackal or God would push me into the endless Night entirely and irrevocably, for all eternity. ‘If it is the same to Thee, then reject me,’ I whispered, ‘but let Jackal stay with me forever.’

‘I had gotten a Pinocchio book,’ Jackal continued. It was the first book of my own. And my father built a dollhouse for my sister Margriet. Not that it looked like anything, but it was still fun. It even had little paintings in it. And those paintings were the pictures from my Pinocchio book.’

‘Life is really unbearable and impossible to live, Jackal,’ I said softly. I spoke even before I had contemplated my words, but now that I had, I knew I meant it, deeply and painfully, with my entire heart, and that I had not said it out of boredom, nor to be funny, nor to mock Jackal. He was now standing at the window. It did not rain yet. A lead sky hung over the city. ‘In bed, with each other, and we’ll never get out,’ I thought.

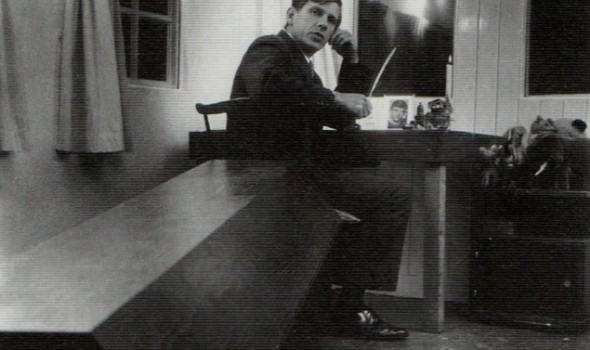

I saw how the eternal light of the autumn afternoon illuminated Jackal’s hips and put the arch of his back not in the twilight, but made it stand out quite clearly. Maybe he wore the same clothes as in the photograph he had shown me once, on a merciful day, in which he, seventeen or eighteen years old, had sat on Santa Claus’s knee at a Yuletide celebration, for fun, surrounded by the branches of a Christmas tree, that were decorated with sparkling death snow, silver death lanterns, glass death clocks and the golden, fallen hair of the Angel of Death. It was actually impossible, so many years later, but I wanted to see it this way and it was how it ought to be, that the dark velvet trousers he was wearing now were the same as the ones he had worn in that photograph, resting warm and tight on the knee of the undignified creature of masquerade, and that this would be equally so for the gray striped shirt, and ah, as well, if it pleased God, for his incomprehensible sleeveless knitted sweater, checkered black and grey, a labyrinth of love which would remain a mystery forever, and which he was wearing now, and which, as he rested his elbows on the windowsill, was just slightly pulled up, up to half a palm’s width above his waistband. I loved Jackal, and I was condemned to love him more and more, as long as I would live, but I could never tell it, nor express or show it, the way it was and the way it consumed me.

‘I am dust and ashes,’ I spoke, as one in a stupor. I stood up and got a few steps closer to him. Jackal’s figure had something indisputably imperative, almost majestic about it: even at his young age, one could clearly tell from the way he looked that his father had once been the second most Important person in the country. ‘Allow me to take off your clothes,’ I whispered. ‘May I see you standing naked? I will fold everything up very neatly.’ I now stepped very close to him. His breathtaking, voracious mouth with the big boy lips, which still also were those of a man, opened slightly, and his mouth curled, as if readying itself for devastating mockery, but he said nothing.

With trembling fingers, staring outside as if deep in thought, in order to hide my ardent longing to behold his body, I started unbuttoning his shirt under his sweater. Jackal allowed me to have my way, lifting his arms to let me slide his shirt and his sweater off his upper body. I lay them, like the ermine mantle of a young king, over the back of a chair, which was actually a throne. How could it be that Jackal reigned by denuding himself, whilst for all other mortal beings nakedness made them defenceless? As I continued undressing him, it was as if he became even mightier, more merciless and cruel.

I had removed his shoes and socks, and now I slid his dark, tight school pants down from his hips and legs, slowly, as if in a silent act of ceremony, whilst I knelt and took on the servile posture of a penniless tailor in a fairytale, reverentially supporting each of his feet, to let him step out of both of his pant legs. I laid his trousers over the armrest of the chair, in such a way that the tender bulges in the back, where the fabric had been granted the task to hold and warm Jackal’s buttocks and protect them against the unchaste and ravishing looks of men who harboured deviant desires, remained very clearly discernible in the material, which was still warm.

Jackal now stood completely bare, with the exception of his light blue, tiny imitation silk underpants, which traced his remarkable masculine shapes with exceptional fidelity. I looked at his Love, which could be called covered, but hardly concealed, considering its size, that I wanted to see rise and rear like a beautiful predator disturbed in his sleep, with all the longing of my heart that was eternally addicted to Jackal. After I laid down his velvet trousers over the chair, I again came close to Jackal, and my hands reached for the elastic cord of the last small piece of cotton that still covered the Truth, but Jackal did not wait for me, and with a few swift gestures removed the final curtain that still covered the Mystery of all mysteries, and which stretched over his blond Member in a tender, heavenly blue glow. His nakedness was as dizzying as it had been almost a year ago during our first encounter, when I had started to undress him with the same shyness, almost without daring to say or ask anything, because how could a Boy like him ever love someone like me?

I began touching and stroking Jackal with the same shiver of insecurity as I did back then: just like then, I could not find the courage to touch his belly right away, and I first touched and caressed his boy neck, but while doing so I had to look, whether I wanted to or not, at his rider’s hips and his dark, enormous sex.

‘If I seek out a boy and give him to you, Jackal,’ I began uneasily and with a slightly hoarse voice, because how could you know in advance how it would unfold, ‘then it should be a boy with a narrow, shallow groove and a small cave, but with a big mouth: so that he may nicely scream and bawl with pain, and cry, while you slowly work your way into him from below.’ I now touched, in proud reverence, the lower part of his back, and felt with my fingertips the tender parting where his posterior began, and then, barely touching his skin, with the back of my hand I caressed both the arched indentations at the outsides of his tight, motionless boy buttocks, while I breathlessly kept looking at his dark groin.

Jackal’s buttocks tightened more vigorously under my touch. His breath came deeper and heavier. I saw his weaponry rise with little jerks, and exaltation made my timidity abate. I knelt down to kiss the arms under which I would want to serve him forever; I blew cautiously on this improbably large horn of love and abundance, and I felt that I was lifted up and carried by an inaudible music of the spheres, which filled the entire universe.

—

Continue: Third chapter

Many thanks to co-translators Jaason von Banniseht en Mireille Mazard