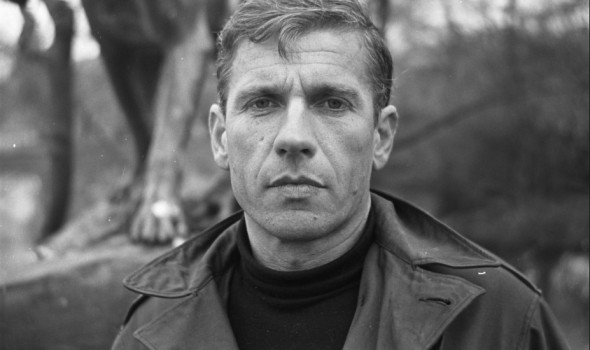

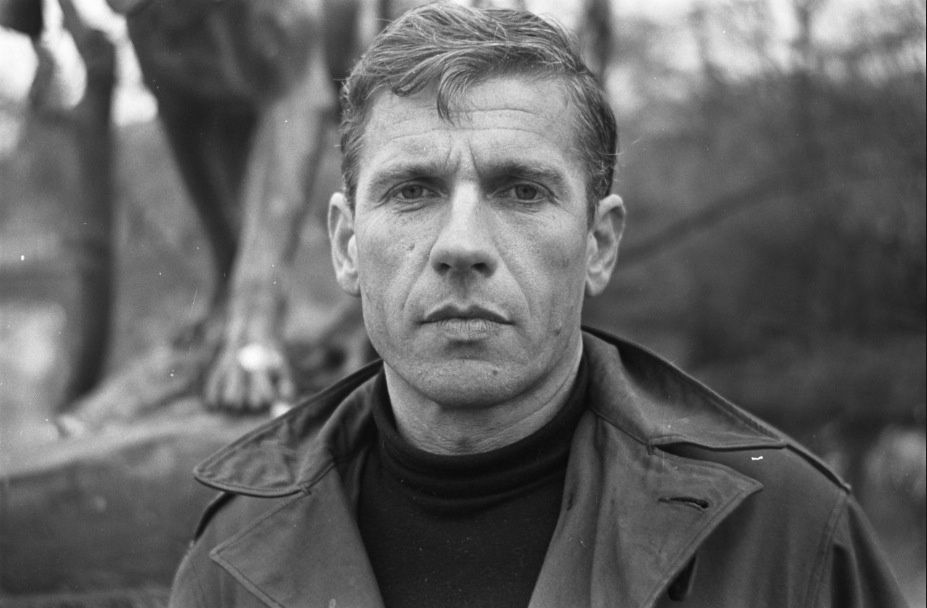

‘It is beyond doubt that I am evil’. So reads the first sentence of the previously untranslated novel A circus boy (1975) of Dutch writer Gerard Reve (1923-2006). The reader who thinks Reve is kidding, await quite a few shocking passages. I translated this novel, which has the same dark mood and black humor as all of Reve’s work, but uses a cunning, thought-provoking narrative trick in the final chapter.

The universe of A circus boy could have been a co-creation of Marquis de Sade and Louis Ferdinand Céline, with production design by the Grimm brothers. It’s gloomy and dark, but not nihilistic: romantic longing pervades all things, and salvation is desperately sought. Our hero toils and stumbles his way through life, aware of the nearness of death, blundering in his attempts at finding love. Relief is provided by the author’s use of black humor.

The first chapter of the novel is a prologue in which the protagonist declares himself, in a magnificent style and with biblical force, to be an untimely born, wicked to the core. In the second chapter we meet him decades later, in the love bed in the tower chamber of his castle, with his boyfriend Jackal, whom he tells lascivious fairy-tales.

Only late in novel we learn what crime our protagonist has committed, in his days as a young truck driver, and why he feels so guilty. The entire ninth chapter is a rape scene from the perspective of the protagonist violating a teenage girl. It is brilliantly written and as painful to read as the notorious rape scene in the movie Irreversible is hard to watch. Reve pushes us to the limit here, challenging us to stay with our main character and confronting us with our own impulses that urge us to continue reading.

Much later in his life, our protagonist will come face to face with his victim, in a plot twist that revolves around the Queen, Whom our main character is now acquainted with, having become a famous writer. Will his horrible secret be revealed and will he do penitence? Will the tormented conscience of our anti-hero find some kind of peace? Read the last three chapters, a marvelous display of dialogue between the queen and him.

In A circus boy Reve slightly departs from his usual way of structuring his stories. Most of Reve’s books are composed as a chain of thoughts, mostly memories, and memories within memories. These memories are connected through mood, not through plot, and are often concluded with a kind of prayer. Part 1 and 2 of A circus boy unfold in this way. But in the final two parts an actual conflict is presented and settled: a criminal who looks for redemption. Who would have thought, an actual story in a Reve novel? It still might not quite be your average page-turner, but at least there are a series of events which are announced by the writer and which are slowly unfolding, punctuated by teasers and cliff-hangers. Reve wanted to write, in his own words, a ‘kitchen-maid novel,’: a novel that makes his girlish readers (m/f) blush with excitement, eager to find out the details of the plot. (Only once has Reve written a novel more suspense-ridden: The fourth man, a crime story. It was made into a movie by Paul Verhoeven.)

Reve uses a cunning narrative trick in the final chapter, but I have to bite my tongue here. It has to do with a request of the Queen. The implications of this trick are so intricate and ambiguous that it is up to each reader to

judge for himself what the deeper meaning might be. It’s great, devious fun, but it might also reveal Reve’s profound, mystical view of the divine machinery of guilt and salvation. The author himself, in an interview for Belgian television (1975), said:

‘One could say, boasting a little: [A circus boy is] Reve’s Faust. It is a book of big dimensions that has more facets and depth, and is less one-sided than my other books.’

So where comes the circus boy into play? There is none, really. The writer/protagonist admits, in his final dialogue with the queen, that as a writer he feels like a circus boy, pulling off an act to please his audience. The audience watches his acrobatic movements high in the air, admiring him, half hoping for his fall, all the while enjoying the entertainment. This confession of the writer comes soon after the sort of-confession his protagonist makes about his crime. Again, it is an interesting narrative circus act, where the protagonist/writer and the actual writer overlap. Although, strictly speaking, it is his protagonist who utters the words, we feel that Reve is including himself in his own story here, making a confession about his authorship.

So on a certain level, A circus boy is a story about writing, about the art of entertaining an audience. We see this self-referential theme often with seasoned artists: as their fame becomes an important factor in their lives, and as they become more conscious about how their art works, they naturally begin including the relation with their audience in their work: it is an interesting source of conflict. When Reve wrote A circus boy, he had been a writer for almost three decades, the last decade of which had been very succesful. In the mid-seventies he had become nothing short of a national celebrity, even with his own bizarre tv-spectacle.

On another level, this is a highly fictionalized and romanticized autobiographical novel. For sure, Gerard Reve did not live in a castle, but in a primitive, self-built house on a patch of wasteland in the south of France. He was never a truck driver in his youth – he used to be the penniless writer – nor did he visit the queen on a regular basis. And let’s hope he never raped a teenage girl. But all this drama is an example of Reve’s tendency, blossoming in the Seventies, to create a highly dramatized, decadent version of his own life.

So is this a very self-conscious novel, is it about the nature of Reve’s authorship and the fictionalized account of his life? Should we treat it like a Charlie Kaufman script? I believe not. Sure, the final chapter is a nice tease, and a thought-provoking ending of a book that needs a worthy pay-off. But apart from plot structure, this work of Reve, as all of his novels, is about mood. There will be readers who catch that mood, because it resonates, and there will be others whom it will escape completely. If it resonates, the reader enters a state of fever and wants to keeps reading, to stay in that mood and have it amplified, not caring so much about plot.

This mood arises from a way of perceiving the world and wanting to be saved from it. It is about being acutely aware of the senseless details of one’s immediate surroundings and the wish to escape from it. It is about the underlying, desperate feeling ‘that everything was inescapably horrible but that the worst was yet to come.’ (chapter 6). It is about the hyper-realistic, apparently futile details of a turning weight of a clock, whose motions the protagonist is forced to see in every detail, while performing the brutal and senseless act of love with ‘Harry’ (chapter 4). Perceiving a thing he does not desire, doing a thing he does not desire, then remembering another thing he does not wish to be reminded of, and all the while hoping, begging to be saved from this horrible reality.

Gerard Reve has won all major Dutch literary prizes, but he has hardly been translated into English (apart from Parents worry, not available anymore, and the short novel Werther Nieland, included in The Dedalus book of Dutch fantasy). In the Netherlands, Reve has published books that, since the Sixties, have consistently sold well, and he has gathered a following with an almost religious fervor.

I consider it a great literary injustice to Anglo-Saxon readers that they are denied the chance to read his work.

This is the reason I have translated A circus boy. Enjoy.